For anyone who manages a Texas farm or ranch, water is more than a utility — it’s a vital, often complex resource that can directly affect your land’s value, productivity, and long-term sustainability.

Whether you're irrigating crops, filling stock tanks, or relying on groundwater for domestic use, understanding Texas’s water laws is central to maintaining compliance and protecting your rights.

This article will explore the core components of Texas water laws, from surface and groundwater rights to conservation practices and legal distinctions that affect landowners.

What Are Texas’s Water Laws?

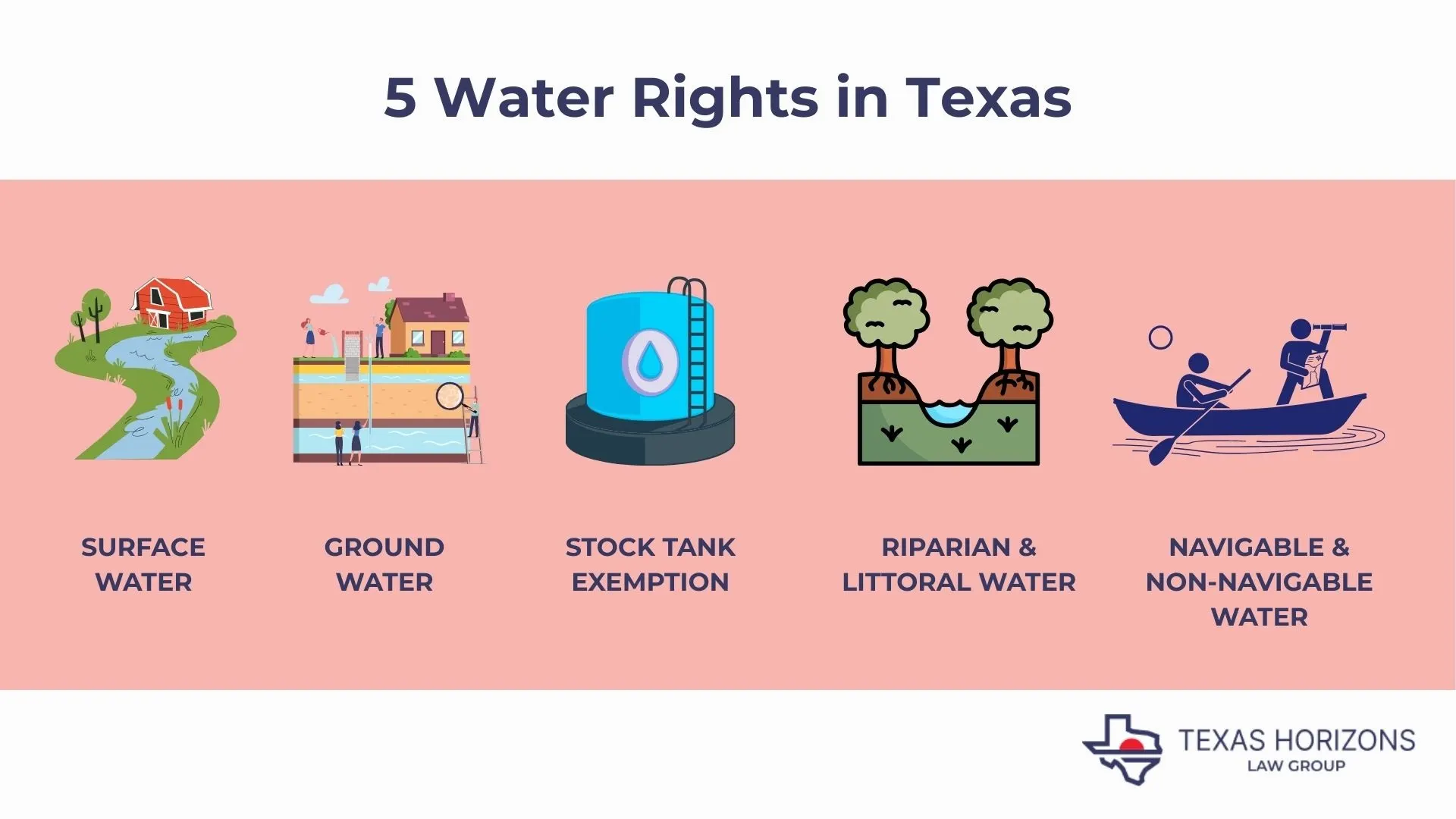

Water law in Texas divides resources into two basic categories: what flows above the surface (surface water) and what lies beneath it (groundwater). This legal distinction means that the rules for using each type are different.

Surface water — which includes rivers, streams, and lakes — is owned and managed by the State. To use it for anything beyond basic household or livestock needs, you generally need a permit from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). Exempt uses under Texas Water Code §11.142 (domestic and livestock use from streams on riparian land) do not require a TCEQ permit.

This system follows what’s known as the “prior appropriation” doctrine, where rights are granted based on the order in which they were obtained. The oldest permits, often called “senior” water rights, take priority during dry periods or times of restricted access.

This framework matters a lot in practice. Your location within a specific river basin (such as the Brazos, Concho, or Rio Grande) can influence your access to surface water in Texas. The state manages water rights within each basin, and availability depends on regional supply, seniority of permits, and local conditions. It’s also important to check to see if the water rights in a particular area have previously been adjudicated by the State courts.

As such, if you're purchasing land or planning a large-scale agricultural operation, knowing where your property stands in the water rights hierarchy is essential.

Surface Water Rights

Texas surface water belongs to the public and is administered by the state. If you're planning to divert water from a stream, construct a reservoir, or irrigate crops using water from a lake or river, you'll need a permit from the TCEQ.

Obtaining a surface water permit involves:

- Demonstrating that the use is beneficial (e.g., for irrigation, livestock, or domestic purposes).

- Submitting an application detailing the location, amount (in acre-feet), and intended use.

- Participating in public hearings and responding to any objections from nearby water right holders or communities.

Failure to secure proper authorization may jeopardize your existing water rights or lead to fines and legal action. Each permit is tied to a specific location and purpose, so if you’re making changes, like transitioning from irrigation to wildlife management or expanding for other purposes, an amendment may be necessary.

Groundwater Rights

In Texas, water that exists underground (such as water drawn from wells) is considered private property in most cases. The state’s legal approach, known as the “rule of capture”, gives landowners broad rights to pump groundwater from beneath their own property, even if doing so lowers the water table or impacts neighboring wells. However, usage may be subject to restrictions imposed by Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs), and is limited by common law doctrines prohibiting waste, malicious conduct, or negligent contamination.

This hands-off policy is unique compared to many other states and has long been a cornerstone of rural land use, but it’s not entirely without oversight.

Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs) have been created in many regions to monitor aquifer levels, set rules for pumping, and promote long-term sustainability. These local districts can impose well-spacing requirements, set limits on how much water can be withdrawn, and require landowners to report their usage.

If you’re located in an area governed by a GCD — and many agricultural zones are — it’s important to review their guidelines before installing a new well or scaling up your water use. While the rule of capture gives you wide latitude, local regulations may still apply to ensure the responsible use of this shared and precious resource.

Surface Water Rights vs. Groundwater Rights in Texas

The Stock Tank Exemption

One of the more favorable policies for landowners is the “stock tank exemption”, which allows private construction of dams, ponds, and small reservoirs without going through the full TCEQ permitting process.

Here’s how it works:

- You may construct a pond, dam, or reservoir that captures up to 200 acre-feet of water per year.

- The water must be used for domestic and/or livestock use, fish, or wildlife management.

- The water must be impounded on your property and not exceed the volume threshold.

- This exemption under Texas Water Code §11.142(a) only applies to privately constructed reservoirs on one's own land for domestic/livestock use, not for irrigation.

This exemption enables many Texas ranchers to enhance their land's utility and value by creating surface access to water without burdensome regulation, provided it's used lawfully and remains within permitted limits.

Riparian and Littoral Water Rights

If your property borders a stream or river, you may enjoy riparian rights, or the right to reasonably use water adjacent to your land. However, these rights come with responsibilities — your use must not impair downstream users or cause harm to the source. Riparian rights were generally extinguished in 1967 unless claimed through the water rights adjudication process, a process which is now governed by the prior appropriation doctrine discussed above.

Common uses include:

- Irrigation

- Water for livestock

- Domestic purposes

Similarly, littoral rights apply to landowners next to still bodies of water like lakes or ponds. In such cases, property owners often own the land beneath the water out to its median high-water mark and may build docks or other structures, provided they comply with local rules.

Whether riparian or littoral, water use must remain reasonable, and disputes with neighbors often come down to case-specific facts.

Navigable vs. Non-Navigable Water Rights

Whether a particular body of water is navigable or not can affect both access and ownership:

- Navigable in fact: A waterway large and deep enough for transportation.

- Navigable by statute: Often based on width (e.g., 30 feet or more from bank to bank) as defined by state law.

Public rights apply to navigable waters. While adjacent landowners may own the surrounding land, the public typically has access to the stream bed for recreational activities, such as kayaking or fishing, provided they access it legally (e.g., via public parks). The beds of navigable streams are owned by the state, but adjacent landowners may still restrict access if there's no legal public access point.

By contrast, non-navigable waters are considered private. If a creek running through your property is classified as non-navigable, you’ll have more control over how it can be used, including prohibiting public use and potentially qualifying for the stock tank exemption.

Managing Water in Times of Drought

Drought is a constant concern in Texas, making water conservation crucial for both landowners and the broader community.

Key conservation strategies include:

- Installing precision irrigation systems that reduce waste.

- Planting drought-resistant crops for enhanced resilience.

- Monitoring soil moisture to optimize water use.

During extreme droughts, mandatory restrictions may be implemented, especially for irrigation or non-essential uses. Participating in conservation efforts is not only a civic duty but can also protect your long-term water supply and demonstrate good faith if conflicts arise with neighboring landowners or government agencies.

How to Buy Water Rights in Texas

In the Lone Star State, buying a water right involves acquiring an existing permit to use surface water, which is owned by the state. You aren’t buying the water itself, but rather the right to use it. There are two main ways to do this:

Purchasing an Existing Water Right

Acquiring an existing water right is the most common course. You can buy a water right (either with a parcel of land or as part of a separate transaction) from the current holder to have the existing permit transferred to you. You must then file a Change of Ownership form with the TCEQ to officially update the records.

Applying for a New Permit

If there is no existing right, you can apply for a new permit by contacting the TCEQ. This is an involved process that requires you to demonstrate a beneficial use for the water and prove that enough unappropriated water is available in the source.

How Much Are Water Rights Worth in Texas?

The value of water rights in Texas varies widely based on location, availability, intended use, and seniority. In high-demand areas, rights can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars per acre-foot. In regions facing drought or with limited access, the cost may be significantly higher.